research

Comparative Humanisms: Secularity and Life Stances in the Post-War Public Sphere

Jeffrey Tyssens & Niels De Nutte

Introduction

In this article, we plan to compare the historical development and current configurations of secular humanism in Belgium, the Netherlands, the UK and the USA, the four countries that have been treated in this book. As was stated in the introductory chapter, the secular movements of these four countries were all active charter members, in 1952, of International Humanist and Ethical Union (IHEU), recently renamed Humanists International (HI). 1 From a long-term historical perspective, this points at a redeployment of the core of the international secular movement. Before 1940, the classical freethinker movements and their diverse allies (ethical societies, freireligiöse Gemeinden etc.) were mainly, though by no means exclusively, located in Catholic, ‘Latin’ parts of the world, Belgium being the permanent host country of these groups’ international federation.2 After 1945, international freethought did not disappear but it was largely marginalised, as we will see. With the start of IHEU/HI, the focus shifted towards a north-western zone with a culture closer to the Anglo-American sphere. Belgium did remain an important international player in this constellation, but lost its hegemonic position: after the Second World War, it was mainly the Dutch humanists who took the lead, the Americans providing the financial means of the international organisation.3

From a predominantly French-speaking collective before the Second World War, with its strong references to the traditions of French “laïcité”, post-war international (secular) humanism developed in a much more English-speaking context, referring largely to very different religious (i.e. predominantly protestant) and institutional configurations. Alongside two large Anglophone countries, French had now turned into a relatively small language in the humanist sphere, present in Belgium only (at least in the first decades), Dutch now becoming more present than in earlier days.4 Different “national” vocabularies were at stake in these settings and inevitably led to major difficulties in translating concepts and their particular historical connotations. Is “laïcité” synonymous with “secularism”? Not necessarily. Compared to France, the concept of “laïcité” even developed into a very different notion in the French- speaking part of Belgium, coming closer to the notion of “vrijzinnigheid” which in turn came to mean different things in Belgium (or Flanders more in particular) than in the Netherlands.5 Similarly, the notion of “humanism” received different connotations in the respective countries and/or languages: with adjectives such as “secular”, “modern” etc. being added to the notion or not, the concept could receive more exclusive or more open definitions in different geographical and historical settings. Even the notion of “secularism” has received various explanations in different countries, Anglophone or other.6

The four countries offer quite different contexts with regard to their respective party systems and their particular connections to civil society. Important variations in their religious background are at stake as well. The institutional relations between church(es) and state have been defined in profoundly different ways. The Netherlands and Belgium both have a multi-party system (as a result of proportional representation). They have similarly generated a pillarisation of society at large – we will elaborate upon this concept later in the article. Depillarisation phenomena transforming this constellation have occurred since the late 1960s in the Netherlands; somewhat later and more gradually in Belgium.7 Belgium was a predominantly Catholic country but has since become largely secularised. The UK, the Netherlands and the USA developed strong protestant cultures, but in all cases with considerable Catholic minorities (sometimes with a strong presence in particular regions, sometimes being carried by specific ethnic groups).8 In the Netherlands, Catholicism eventually even became the single largest denomination. Church-state relations in the four countries span the whole variety from a relatively strict separation, over heritages of concordatory regimes to the persistence of an established church. The four countries that we are treating all possess important non-profit sectors with considerable numbers of paid staff, but they have developed very different cultures with regard to private donations as well as with regard to state subsidies for this kind of voluntary societies. Belgium hardly has any tradition of individuals sponsoring associative life, but state funding of the latter is considerable. The USA has strong traditions of private sponsoring and hardly any public support of voluntary associations. The Netherlands and the UK have – or have had – both.9 In a similar vein, different roles have been attributed to public authorities with regard to various welfare sectors including health care. Media landscapes are very different as well. Broadly speaking, the USA has generated a very different configuration than the three European countries where public broadcasting has been much more present, even if neoliberal policies have tended to curtail at least the role of central authority as an organiser or as a regulatory force.

All these dimensions,10 contextual, terminological, organisational and others, will frame our attempt at a comparative interpretation of different strands of post-war organised humanism, mainly by dint of a problematised conceptualising of “identity”. We will discuss (Spanish sociologist) Castells’ notions of “legitimising identity”, “resistance identity” and “project identity” with regard to these humanist “spheres” (as Stefan Schröder, Religionswissenschaftler, would no doubt qualify them),11 for who the notion of a common, “religion-like” identity (as thoroughly explained by Quack, Schuh and Kind)12 may seem to be debatable in the first place. To what extent do these spheres, which even struggle to become a genuine movement, indeed sufficiently possess unique identifiers that are deeply shared? Is the idea of secularism not inherently contradictory to the notion of a life stance as a distinctive identity or, more in particular, to the idea of a community to which the former concept is closely related? The proponents of French “laïcité”, who may just be quite indifferent to the qualification as humanists and who firmly oppose all kinds of “communautarisme” or “communalism”, whatever its identifiers may be, would definitely confirm that this is indeed a contradiction. Current strategies of several humanist organisations – e.g. by seeking or obtaining formal recognition and funding equivalent to established religions – do seem to point in a different direction though. And what about those humanists who do not per se define themselves as secular?

Humanisms and their path dependency

As we already suggested, (secular) humanism did not simply emerge in a void. With the exception of some pre-1940, sometimes rather marginal, tentatives to foster a humanist renewal,13 organised humanisms are largely a post-war phenomenon. They had been preceded by freethinking societies whose history dated back almost a century. After 1945, some of these had severely weakened (e.g. the erstwhile strongly developed Belgian societies, that were quickly reduced to a limited and somewhat aged membership). Others, such as the Dutch Dageraad, did not do all that badly after 1945, but did not become a large movement either. Before 1940, international freethought had entered into a crisis because of the difficult fusion of mainstream organisations and their pro-USSR, communist counterparts.14 In the cold war climate after the Second World War such cooperation became highly problematical. The issue has hardly been investigated, but it does seem that the traditional organisations or even their successors were perceived as too radical, too much to the left, even if their leaders were not necessarily communists or fellow travellers. Sometimes things were even more clear cut, as was shown in 1957 when IHEU refused membership to the French Union Rationaliste because of its communist leanings.15 However that may be, the “pre-history” of post-war humanism remains important as its new organisations could operate, at least up to a certain extent, as continuations of the traditionally combative opponents of churches and clericalism. But that was not necessarily the case for all, the traditions of the ethical societies being very different, far less struggle- bound and more quest-oriented as they were. In any case: the new post-war context, with the recent past of Nazism and the current threat of the Soviet bloc, imposed very different challenges. For many, totalitarianism appeared as more of a menace than religion. But how did this translate into the different national settings? Outcomes were eventually very different. It appears furthermore that this cold war logic lost much of its impact after about a decade or two.

The Dutch humanists, quickly outgrowing their predecessors of De Dageraad, started focussing upon community building (together with religious humanists for whom the old-style freethinkers had no place) and its practical underpinnings in social work on a non-religious basis for potentially vulnerable groups.16 In Belgium, traditional anticlerical tendencies did not disappear, but a more moderate stance did prevail nevertheless. Church-state separation-oriented discourse weakened, and issues related to ethics and humanist services for the non-religious gradually became more of a core of the movements’ self-definition. The north and the south of the country showed different paces in this development. For evident linguistic and cultural reasons, the Flemish societies had been directly influenced by the Dutch model right from the start. Their Francophone counterparts echoed the French model much longer but eventually adapted to a Dutch example as well.17 In both cases, state funding was requested and eventually obtained, with very different modalities compared to the Netherlands.

In Britain, the older set of secularist groups, represented by the National Secular Society (NSS) and different strands of ethical culture associations, were joined in 1963 by the British Humanist Association (BHA, currently Humanists UK). The BHA, inspired as it was by earlier American humanist societies, was organised as a direct result of the Oslo IHEU-conference the year before.18 This new humanist structure was the legal successor of the Union of Ethical Societies (established in the final years of the nineteenth century) and started focusing more on community building for humanists and the offer of humanist services. In the context of the 1960s radical politics, the BHA paradoxically reframed classical secularism into humanism and no longer presented its stance as a mere rejection of God or organised religion. The NSS for its part still focused (and focuses) on the protection of the public sphere against religious influence. If the BHA countered religious interference with society, it tended to do so more specifically in defence of women’s rights, gays, or single political issues such as the 1960s Suicide Act. The BHA also supported causes of a quite different nature, like e.g. the peace movement.19

In the United States, humanism emerged as the heir to nineteenth-century radicals, both religious and irreligious. It grew out of the Unitarian movement: this religious denomination aimed to find a way to dilute dogma to a level acceptable to a less devout and more sceptically inclined audience. By the second decade of the twentieth century, this endeavour led some of its ministers to non-theism. Post-war American humanism was originally more directed toward a high-level intellectual debate on the philosophical or psychological foundations of humanism and had a particular propension for defending a scientific perspective against anti-scientific or pseudo-scientific tendencies that were more prominently present in American society than in Western Europe. As of the 1970s, American humanists became more militant within society at large, definitely as a reaction against the growing impact of the Christian Right upon the polity within the United States, where the latter directly challenged the constitutional separation principle and legal secularism on diverse levels (the Lemon test etc.), not without some success.20

Humanisms and public governance

In all countries, the (non-)availability of a political “conveyer” of secular and humanist associations is a problematic issue. In Belgium and the Netherlands, as we already suggested, the specific format of the countries’ pillarisation is important to understand this. Pillarisation refers to the formation of highly integrated, ideologically oriented networks of very diverse voluntary organisations that are connected to a political party and organise the social lives of the rank-and-file from cradle to grave with the aim of warranting loyal voting behaviour; the pillar’s organisations absorb functions that could just as well be performed by public authorities but who are conveyed to these private actors who are (largely or completely) funded by those same public authorities. Pillars hence become major sources of social and political power within their respective societies and tend to monopolise effective ways of political agenda setting in the main areas of decision making. In none of the countries, a “secular pillar” ever took shape.21

In the first Belgian labour party (1885) – an indirectly structured federation of member societies – socialist freethinker groups had been affiliates, but party strategies of electoral opening towards Christian workers eventually led to a de facto expulsion in 1913. Henceforth, within the Labour leadership, only some individual sympathies remained. In the liberal world, where pillarisation phenomena were weaker in the first place, no structural links ever existed, only informal connections through individual MPs mainly. This absence of a structural integration with political forces was inherited by post-war humanists: only individual “relay actors” in those political families could be counted on, at particular occasions, in favourable constellations, to have humanist demands given some voice on the political scene.22 The contrast could hardly have been bigger with the powerful Catholic pillar, which proved to be not only a highly efficient tool to cope with secularisation and keep considerable numbers of the non-practising attached to the confessional parts of Belgian civil society, but it also was very effective in promoting confessional interests on different levels of decision making, mostly through the Catholic or later the Christian-democratic parties. In the last decades, as far as the rank-and-file is concerned, de-pillarisation has become very real in Belgium: individual adherence to pillarised organisations became oriented largely to service consumption without translating this any longer into party loyalty. However, the large pillarised concerns that offer these services have remained influential players and have often kept an ideologically conforming staff at management level. This goes mainly for the Catholic pillar, the other two appearing to be ever less integrated.

In the Netherlands, the freethinkers first had a similar tendency to try and find political expression through the SDAP, the social-democratic party, but here again, strategies to draw believers into the socialist electorate led the party to a principled decision (at the Groningen party congress of 1902) to be politically neutral towards religion and to drop any tendency towards militant secularism.23 The relation with the liberals was as good as non-existent: even the left-leaning ones of the Vrijzinnig- Democratische Bond at best only sympathised with freethought societies when the latter’s constitutional rights were denied by confessional governments.24 Hence, freethinkers and humanists did not really become a structural part of a non- confessional (c.q. the social-democratic) pillar in the Netherlands. The consequences were very similar to the ones we noticed in Belgium. In contrast to confessional actors who had their structural links to the Protestant and Catholic pillars, Dutch freethinkers and (secular) humanists could only count upon sympathising MPs of a set of parties: some social-democrats (SDAP and later the PvdA), a number of the left-leaning liberals of D66 (as of the late 1960s) and some members of Groen Links (a conglomerate of different left wingers coming from older communist, pacifist, radical and ecologist parties). One can argue that this mirrors the near- complete disappearance of the old pillarised logic of the Dutch political system. Indeed, de-pillarisation seems to have transformed Dutch society more profoundly than the phenomenon qualified with that same concept in Belgium: Dutch pillars show strongly decreased memberships and failing loyalty production towards their political parties. They seem to show an even more pronounced diminishing of their ideological cohesion and all seem to be eroding, i.e. in a more encompassing way than in Belgium.25

The UK and the USA have had no such pillarised constellations. In Britain, secularists, the ethical societies and later humanists always had a quite ambivalent relationship with the parties which could have been potential allies.26 Through well- known secular leaders such as Charles Bradlaugh MP, a connection with the left wing of the Liberal Party did exist but secular forces were hardly the only ones competing for influence among these radicals where Christian denominations, dissenting ones notably, were very clearly present as well. The earlier secular militants within the working classes or the lower middling orders often had socialist leanings but the integration with the political structures, certainly with the Labour party, remained weak. Labour was much less prone to anticlericalism than the continental socialist parties and had a considerable following among Christian labourers as well.27 This implied that the political voicing of secular interest tended largely to fade away towards the end of the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth.28 Post-war humanism did find some support in the All-Party Parliamentary Humanist Group, started in the 1960s, and which is joined nowadays by some 100 MPs.29 This way of dealing with political agenda setting and decision making clearly reflects the impact of a liberal tradition, as David Nash argues, where lobbying and single-issue politics were very much at the core of strategies towards public authority, rather than structural integration with any political party. These strategies focus less on serving a particular constituency rather than fostering broader enabling targets for individuals at large. However, it does not seem that this parliamentary humanist group is a very active nor a very influential collective, some individual engagements notwithstanding.30

Militant seculars and humanists in the USA have long held quite timid views on giving their philosophical stance a political voice. For a long time, both the Democratic and Republican parties and their members of congress, state legislatures, etc., however much they may have held a “big tent” approach of their political constituencies, were hardly very keen on identifying too explicitly with groups that could potentially be dismissed as atheist and the like. For a long time, secular and humanist groups affirmed to have had an educational, not a political mission. Furthermore, their status as non-profit organisations imposed limitations upon their possibilities of supporting candidates.31 The small movement’s dimensions (incomparable to e.g. the evangelicals’ weight in the Republican party since several decades) were not of a nature to give secular humanism many possibilities to act more or less effectively as one of the “small lobbies” in DC or in the state capitals. This structural weakness must be related as well to the fact that American “nones” even today do not utilise their full voting potential. Although they constitute almost a quarter of the population, they account for only 17 % of voters in the 2018 Midterms. This stands in sharp contrast to white evangelicals with roughly 15 % of the population but 26 % of the voters.32 However, the growing impact of the Christian right eventually fostered the growth of a formal political advocacy group of secular humanism, viz. the 2002 Secular Coalition for America, which has since allied an ever more representative set of atheist, secular humanist and ethical societies for its DC and state chapters.33

Humanists, welfare and counselling

The offer of services in welfare and counselling, with all-round counsellors (existing in the Belgian case) or, with a more specialised staff catering to needs of the nones in hospitals, prisons, army and police units, airports and universities, constitutes one of the major innovations introduced by post-war humanism.34 This practical humanism – prioritising service over anti-clerical critique – is inherent in twentieth century atheists and humanists.35 Because of the monopoly religions held upon services of this nature for a very long time, a particular vocabulary is often used to qualify these services or the staff members and volunteers performing them. In an effort to strengthen humanist professionals, European Humanist Professionals has existed as a network organisation since 1994.36

In English, the key concepts are “chaplain” and “chaplaincy”. Although these are used in Britain and are partly seen as an unproblematic extension of its parochial system, Humanists UK uses the alternative term of “pastoral support” arguing that the religious connotation of “chaplaincy” acts as a barrier to aid-seeking nones.37 As early as the 1960s, provisions for members of non-established churches were sought in Britain using the number of adherents as a point of reference. The Belgian humanist organisation was spurred on in much the same manner, as we will see.38 Non- religious pastoral support, however, has only recently developed in Britain, though markedly successful.39 In the span of only six years, Humanists UK has managed to create a Humanist Chaplaincy Network (2013), arrange humanist pastoral support in prison (2014) and have the National Health Service (NHS) state that ‘non-religious people should have the same opportunities as religious people to speak to someone like-minded in care settings’.40 In 2018 the first humanist to lead an NHS spiritual and pastoral care unit was appointed.41

Things were quite different in the United States, where humanist chaplains have been appointed at up to eight universities since 1974, most prominently at Harvard.42 Much like it is the case in British health care institutions, where chaplains work in a multi-religious team. The only other sector which American humanists seem to try and access is that of the armed forces. Since 2011, the AHA and Military Association of Atheists and Freethinkers (MAAF) have unsuccessfully struggled to appoint a non- religious chaplain as they are not endorsed by what is called a “qualified religious organisation”.43

As a result of their common pillarisation logic, Belgium and the Netherlands have had an early start in what they call ‘geestelijke c.q. morele begeleiding/ assistance morale’.44 This has led to humanism being represented in a variety of health and welfare contexts, although not in a manner equivalent to their religious counterparts.45 Dutch humanists have ‘geestelijke raadslieden’ in penitentiaries since 1955 and in the military since 1964. Although limited in number, Dutch humanist counselling has expanded to include hospitals, elderly care and student care. An official master’s programme is part of the Utrecht University of Humanistic Studies. Belgian humanist professionals, “moreel consulenten” and “conseillers laïques”, were similarly appointed to penitentiaries in 1965 and the military only by 1991. Counsellors have also been present in clinics and rest homes since 1970 and at Brussels airport and the University of Antwerp.46 Both Dutch and Belgian humanists are for a large part tributary to their respective state financing models. Their turn to accommodationism for nones and/or desire to be legally recognised as one worldview among others has allowed them to flourish financially. This is something their more uncompromising predecessors did not ambition.

Humanisms and the media landscape

With regard to the potential or actual presence of secularism and humanism in mass media, several sectors are at stake. First of all, with regard to the traditional printed media, it is clear that dailies with clear connections to secular or humanist organisations were highly exceptional and usually had expired long before the post- war period we are treating here. Not even Bradlaugh’s National Reformer (1860- 1893) was a daily newspaper: only the Journal de Charleroi (already in existence since 1838), edited in Belgium’s south, matched that description for a part of its existence, but it had only a regional scope and eventually its secularist engagement faded away in the interwar years. Hence, secular printed media remained relatively marginal and were limited to small circulation periodicals and books or brochures published by societies such as the Rationalist Press Association in the UK or Prometheus Books in the USA. We have no knowledge of any significant ambitions to go beyond these limited printing endeavours.

Things have evolved differently with regard to the modern media of the twentieth century, i.e. radio and television. The contexts were and are very divergent in the four countries. In the Netherlands and Belgium, public broadcasting has long held a monopoly (public television in Belgium and the Netherlands has only had private competitors since the late 1980s). However, pillarisation could impact upon the actual functioning of radio and TV. In the Netherlands, a large part of the public broadcasting time was outsourced to pillarised broadcasting licence holders (the so-called “zendgemachtigde verenigingen”) that obtained time-slots in concordance with their memberships. In Belgium, the largest part of the broadcasting time remained outside of these devolution mechanisms, even if the programmes under the “third-party broadcasters” formula (called “Uitzendingen door derden” since 1979) did allocate some limited time-slots (and some public funding) to programmes by different ideological subcultures, denominations and economic interest groups, as we will see. In the UK, private TV competitors were already present since the mid-1950s, but nevertheless the BBC did hold a more or less hegemonic position in the media landscape for quite some time, even if commercial chains have become ever more present since the 1980s and 1990s.47 In the USA, public broadcasting never even approached anything of a hegemonic position. Since the earliest days of American radio and television, commercial broadcasting was very much present alongside local stations that were to coalesce only later into a larger public broadcasting sector that was to receive federal money as of the 1967 Public Broadcasting Act, alongside other public means and private-origin revenues (ranging from corporate money to individual contributions by the audience).48 This obviously had important consequences for the actual or potential presence of humanists on radio and TV.

Very quickly after the start of public radio in Belgium, freethinker societies obtained some radio time since 1933 (just like Catholic programmes), but the time slots were very limited and the radio talks were often confronted with government censorship. This led to repeated incidents, which echoed even in Parliament.49 A more longstanding and less controversial formula was found in 1955 with the devolutio n of this limited humanist broadcasting time to more autonomous committees (for Dutch- and French-speaking broadcasting) and later to non-profit societies that inherited their assignments: La Pensée et les Hommes (1961) and Het Vrije Woord (1981).50 The French programmes still exist but the Dutch ones have been side-lined in 2015. This was contested because diverse masses and celebrations (from Roman Catholic to Jewish) were still broadcasted. Since then, four humanist programmes are scheduled per year.51 The Dutch humanists tried to enter the pillarised broadcasting system but could hardly do so with a regular radio and TV society: its limited membership would have precluded any significant presence on the waves. However, by adopting the status of a “kleine zendgemachtigde vereniging”, a formula that was open to different smaller life stances irrespective of membership numbers, humanist programmes did obtain a certain place in public broadcasting in 1966, together with the freethinkers programmes of De Vrije Gedachte. Since 1981, broadcasting was entrusted to the Humanistische Omroep Stichting, renamed Human in 1989.52

British humanists had far more difficulties getting something of a participation in radio and TV and never really obtained anything structurally embedded. The 1955 radio talks of Margaret Knight on morality without religion and on moral panic caused quite a controversy and were not repeated since.53 UK humanists have nevertheless requested a place within BBC programming and notably tried to reform series such as Thought for the Day, because of its frequent religious underpinnings.54 Following the 2003 Communications Act, the British government quite explicitly stated that programmes on religion “and other beliefs” should include humanism, but this hardly had any effect. In 2009, humanists sent their own representative to the BBC’s Standing Conference on Religion and Belief (successor of the older Central Religious Advisory Committee), not to everyone’s delight by the way, but that advisory board was relatively short-lived. Humanists have been consulted on programming but without being able to challenge the favoured position of religions.55 This disproportion is somewhat compensated by the relative successes in having celebrities publicly supporting humanist views, on radio or TV or more recently also in social media.56 Humanists in the USA only recently succeeded in organising a presence on radio and television. Since 2006, radio programmes have been offered under the auspices of the Freedom from Religion Foundation. Humanist broadcasting was distributed via Air America until 2010. Since then, six or seven city stations provide this humanist programming.57 Television presence has only existed since 2014 with Atheist TV.58

Humanists building a nonreligious presence

As stated at the beginning of this article, we argue that it is definitely problematic to dub humanist organisations as an identity-based movement. Apart from using distinctly different self-identifiers, which are historically and culturally predisposed to anticlericalism or to a relative lack thereof (humanisms as context-dependent),59 manifestations of organised humanism without exception include a variety of people claiming one or more terms such as “secularist”, “agnostic”, “freethinker” and others. More often than not, humanist organisations are composed of a mixture of tendencies. This is most visible in the American and Belgian cases, with coexisting religious and scientific factions in the former, the latter being divided along the lines of adherence to strict state-church separation or to formal life stance recognition. Finally, in a context of deepening secularisation (at least in Europe)60 and broadened acceptance of liberal ethical standards, modern humanist core values have lately tended to be so commonplace61 that a set of people retrospectively realised they have ‘always’ been humanists.62 For some this led to an explicit identification, for others to no particular life-stance identification whatsoever.

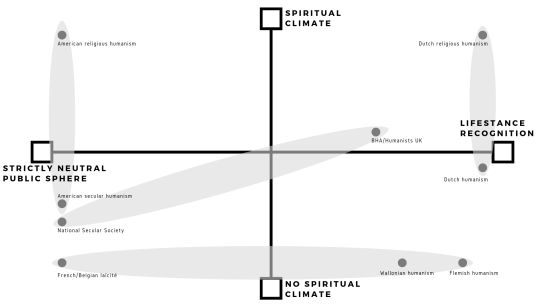

In the diagram following this paragraph we tried to visualise the internal divergences of the humanist spheres, between national cases as well as within them.63 We have thus graphically located these organisations and tendencies in a “field” with two axes: the first one opposes the ambition of life-stance recognition to the pursuing of a strictly neutral public sphere;64 the second one indicates the presence or absence of what e.g. in a Belgian context would be qualified as a “spiritual” climate, but what others would define as “religion-relatedness”.65 The diagram shows relatively broad varieties within national cases, but also leads to observing – perhaps in a counter- intuitive way – that more “spiritual” or “religion-related” forms of humanism do not necessarily lead to desires of lifestyle recognition or, similarly, that highly “unspiritual” varieties of humanism do not automatically imply a staunch support of French-style “laïcité”. One might ask to what kind of common humanist identity such a configuration may lead.

In the introduction, as Richard Cimino and Christopher Smith briefly did in a 2007 article,66 we referred to three notions of identity67 as defined by Manuel Castells in his seminal book The Power of Identity, where he discusses identity’s transformations in today’s “network society”. The point of departure is always a “legitimising” identity, which is ‘introduced by the dominant institutions of society to extend and rationalize (sic) their domination vis-à-vis social actors’.68 In our subject area, this legitimising identity would imply that a “good” national would unquestioningly adhere to e.g. Catholicism in Belgium, the Dutch Reformed Church, to Anglicanism, or in America to a variety of Protestantism, with the exclusion of other religions and freethought. “Resistance” identity is ‘generated by those actors who are in positions/conditions devalued and/or stigmatized (sic) by the logic of domination, thus building trenches of resistance and survival on the bases of principles different from, or opposed to, those permeating the institutions of society’.69 These identities are developed notably by religions which do not fit into this hegemonical frame or which are even explicitly targeted by it (see e.g. the role of the test acts in the British context as a means of excluding “papists”). But it is just as clear that originally, freethought – and perhaps even secular humanism – developed in a very similar way. Freethought societies, humanist leagues etc. passed a considerable part of their history ‘in the trenches’ indeed. Contesting church monopoly on graveyards, claiming secular oath formulas, attacking blasphemy laws and establishing a counter-current of secular schools are some prime examples. Eventually however, seculars moved ‘out of the trenches’70 with projects going beyond mere opposition. This brings us to Castells’ notion of “project” identity, where ‘social actors’ build a new identity that redefines their position in society and, by so doing, seek the transformation of overall social structure’.71 Interestingly, Castells shows that resistance identities can induce project identities, which may ‘become dominant in the institutions of society, thus becoming legitimizing (sic) identities to rationalise their domination’.72

This analytical cycle of Castells needs some discussion though. Indeed, in his approach, resistance identities lead to the formation of “communities”, whereas project identities create “subjects”73 and legitimising identities create “civil society”. This seems to be rather at odds with the history of secular humanist movements. The resistance identities of freethinkers or humanists hardly made explicit a community formation objective, even if this may have been the actual result of their actions in the trenches (even then, the precise delimitations to other identities, e.g. the socialist one, often remained relatively unclear). Project identities in humanist spheres seem to have related in a different way as well: for e.g. Dutch and Flemish humanists, the coming out of the trenches with the concurrent abandonment of an explicit opposition against religion coincided very clearly with a new, explicitly claimed objective of forming a distinct and formally recognised identity. The British namesakes have followed a comparable path but in a non-pillarised society and often with less clear results (see e.g. the BBC issue), which still seems to point at a continuing presence of a resistance identity. Did any of these efforts ever lead to a legitimising identity? This can be discussed, although it seems more appropriate to us that Belgian and Dutch humanisms amounted mainly to an integration into a pre-existing legitimising identity elaborated by others, i.e. with a “humanist” or “non-confessional” community finding a place in a pillarised society whose settings were defined by other identity groups (largely by the confessional ones) and whose opening towards humanists more or less warranted their own continuation.

Although it is often represented in a different way, the French “laïcité” can also be approached as a project identity, as a coming out of the trenches, its goal setting going far beyond the defence of a secular group interest. Indeed, the 1905 Loi de séparation des Eglises et de l’Etat (Law of Separation of Churches and State) was not an extremist plan (the radically antireligious forces had other schemes in mind) but a design produced by secular moderates to allow a new kind of living together of different life stances (hence its first article proclaiming religious liberty) under the umbrella of a shared citizenship within the republic and its set of basic values.74 But no community (outside of the national body politic) had to be constructed in this way, quite on the contrary. One can say that this project identity of the “laïques” as good as immediately merged into a new legitimising identity, i.e. a hegemonic project becoming the new doxa of society, the foundation of a new civil society.

Things become even more complicated when taking into account the American case, where this kind of separation was present right from the start, be it then as part of a legitimising identity mainly directed at securing a protestant national identity opposed to any kind of church establishment. How to evaluate a humanist identity in terms of the legitimising/resistance/project trio if the sequence presumed in the other cases seems to have been turned topsy-turvy? Indeed, the gradual making of a more permeable “wall of separation” seems to lead American humanists, atheists and the like to complex combinations of a fundamental defence of the separation principle with pragmatic approaches aimed more at being treated equally with religious denominations that have more aggressively claimed a public presence since a number of decades.

Finally, we must at least hint at a number of more recent developments where the growth of a globalised society with its new and different (public) presence of religion, notably under the form of Islam, seems to alter some sensitivities in secular humanist groups. Is this leading to a kind of return to the trenches, to a renewed resistance identity? It is sometimes the impression we have when looking at the Belgian case (in a clear parallel to the French one), where debates on e.g. the presence of the Islamic veil in public schools seems to foster a kind of return to more classical, perhaps more combative approaches of secularity (i.e. again the strict separation idea rather than an ongoing acceptance of some kind of modest establishment), even if these approaches show a distinct tension with the strategies that were defended in the last decades of the twentieth century and that have clearly determined the public status of secular humanism today (i.e. that modest establishment stance precisely). What the French have qualified as “le retour du religieux” (alongside other identitarian movements, no doubt) can only have impacted upon the other humanisms as well, as the American case since the 1980s seems to show, but where the response seems to be somewhat different. It remains to be seen if indeed a return to the trenches will result from this momentum and/or if more ambitious goals settings, i.e. a new project identity or perhaps even a new legitimising identity, will be the eventual result.

Footnotes

- At the 1952 Amsterdam founding conference Austria and India were founding members as well, whereas a French delegation participated but eventually declined membership. The participating Austrian society (Gesellschaft für Ethische Kultur) fell on financial hardship and stopped paying its contributions in 1957. As such, it will not be treated here. The Indian Radical Humanist Association is still active today, but not having access to sufficient source material and scholarly literature, we decided not to include the Indian case in our present analyses. We are aware that this causes our text to operate from an ‘Atlantic’ perspective. ↥

- Jeffrey Tyssens and Petri Mirala, “Transnational Seculars: Belgium as an International Forum for Freethinkers and Freemasons in the Belle Epoque,” Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Filologie en Geschiedenis/Revue belge de Philologie et d’Histoire 90, no. 4 (2012): 1353-1371.↥

- Until the late 1970s, the Americans, represented by the American Humanist Association (AHA) and the American Ethical Union (AEU), provided roughly 40-70 % of the IHEU budget. See: Bert Gasenbeek and Babu Gogineni, ed. International Humanist and Ethical Union. 1952-2002. Past, Present and Future (Leusden: De Tijdstroom, 2002), 30.↥

- At first, no French-speaking organisations were present in IHEU. They only appeared as members as of the 1960s, notably with the Ligue française de l’Enseignement et de l’Education Permanente. English eventually became the lingua franca, a fact that French delegations did not always appreciate. See: Rob Tielman, Humanisme als zelfbeschikking. Levensherinneringen van een homohumanist (Breda: Papieren Tijger, 2016), 102-104. ↥

- An article in English on the difference between French and Belgian “laïcité” is: Hervé Hasquin, “Is Belgium a laïque State?” in Separation of Church and State in Europe, ed. Fleur De Beaufort e.a. (The Hague: European Liberal Forum, 2008), 91-110. To improve understanding of the notion “vrijzinnigheid” we refer to the semantic investigation in: Roland Willemyns, De term vrijzinnigheid. Een eerste poging tot semantisch-vergelijkend onderzoek van het woordveld (Antwerp: Humanistisch Verbond, 1980).↥

- In the English language the notion was coined by George Jacob Holyoake. From 1859 onwards, the term flew over to the United States. In the sense of liquidation of clerical rule, the German term säkularisieren was used as early as the middle of the 17th century. See: Werner Conze “Säkularisation, Säkularisierung,” in Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe. Historisches Lexikon zur politisch-sozialen Sprache in Deutschland V, ed. Brunner O., Conze W. and Kosseleck R. (Stuttgart: Klett- Cotta, 1984), 796; Andrew Copson, Secularism: Politics, Religion, and Freedom (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017).↥

- Luc Huyse, De verzuiling voorbij (Leuven: Kritak, 1987); Marc Hooghe, “Vijftig jaar na mei ’68: ontzuiling in de Lage Landen,” Ons Erfdeel 51, no. 2 (2008): 4-19.↥

- In Western Europe, adherence to Christianity has changed from being quasi ubiquitous in 1910 to 69 % in 2010. Meanwhile, the nonreligious represent 23.5 % of the general population. These numbers are matched by religious affiliation in the United States, where one-quarter of the population is religiously unaffiliated. There is, however, a marked difference in the vigour of religious identity and practice, which is still much stronger in the United States. In Western Europe, non-practising Christians are the largest demographic group. See: Robert P. Jones and Daniel Cox, ed., America’s Changing Religious Identity. Findings from the 2016 American Values Atlas (Washington D.C.: Public Religion Research Institute, 2017); Pew Research Center, May 29, 2018, “Being Christian in Western Europe”; Pew Research Center, May 12, 2015, “America’s Changing Religious Landscape”. ↥

- For comparative statistics on national nonprofit sectors, the John Hopkins Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project proves an excellent source.↥

- Some of these, which are not consistently present in all contributions to this book and which may just be very specific to a particular case, will not be studied here, e.g. development cooperation is very important in the Netherlands but hardly existed in the other national examples.↥

- Stefan Schröder, Freigeistige Organisationen in Deutschland: Weltanschauliche Entwicklungen und Strategische Spannungen nach der Humanistischen Wende (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2018). ↥

- Johannes Quack, Cora Schuh and Susanne Kind, ed., The Diversity of Nonreligion. Normativities and Contested Relations (London: Routledge, 2019). ↥

- Jeffrey Tyssens and Els Witte, De vrijzinnige traditie in België. Van getolereerde tegencultuur tot erkende levensbeschouwing (Brussels: VUBPRESS, 1996), 107-109.↥

- Before the establishment of the World Union of Freethinkers in 1936, tensions surrounding the social question were very apparent among freethinkers. After the Great War, the International Freethought Federation (or Fédération Internationale de la Libre Pensée) split into different factions. Fragmentation was caused by accusations that the federation did not represent the working classes. The WUF was a result of the need for a popular front-style cooperation between freethinkers against the rise of fascism. See: Tyssens and Els Witte, De vrijzinnige traditie in België, 101-105; Daniel Laqua, The Age of Internationalism and Belgium 1880-1930. Peace, Progress and Prestige (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013), 101-103; Ben Edwards, “The Godless Congress of 1938: Christian Fears About Communism in Great Britain,” Journal of Religious History 37, no. 1 (March 2013): 1-19.↥

- Utrechts Stadsarchief, 1733 International Humanist and Ethical Union (IHEU), 556-562 Received and outgoing correspondence with various individuals and organizations, 1956-1967 (1981), 1990-1995; Bert Gasenbeek and Babu Gogineni, International Humanist and Ethical Union. 1952-2002. Past, Present and Future, 37.↥

- Bert Gasenbeek and Peter Derkx, ed., Georganiseerd humanisme in Nederland: geschiedenis, visies en praktijken (Amsterdam: Het Humanistisch Archief Utrecht & Uitgeverij SWP). ↥

- Jeffrey Tyssens and Els Witte, De vrijzinnige traditie in België, 123-124. ↥

- Bishopsgate Institute, British Humanist Association, accessed 31 May 2019, https://www.bishopsgate.org.uk/Library/Special-Collections-and-Archives/Freethought-and-Humanism/British-Humanist-Association. ↥

- Samuel Bagg and David Voas, “The Triumph of Indifference: Irreligion in British Society,” in Atheism and Secularity – Volume 2: Global Expressions, ed. Phil Zuckerman (New York: Preager Press, 2009), 92-93.↥

- The Lemon test refers to the 1971 Supreme Court decision in the Lemon v. Kurtzman case invalidating state aid to religious schools in Pennsylvania. The Lemon test “required a law to have a ‘secular purpose’, to neither ‘advance’ nor ‘inhibit’ religion, and not to entail ‘an excessive government entanglement with religion’”. See: Daniel K. Williams, God’s Own Party. The Making of the Christian Right (Oxford, University Press, 2010); Christian Joppke, The Secular State Under Siege. Religion and Politics in Europe and America (Cambridge: Polity, 2015), 86-127; idem, “Beyond the wall of separation: Religion and the American state in comparative perspective,” International Journal of Constitutional Law 14, no. 4 (October 2016): 991, 998-999. The plaintiff, Alton Lemon, was the African American president of the Philadelphia Ethical Humanist Society in the 1960s. See: Thomas Berg, “Lemon vs. Kurtzman. The Parochial School Crisis and the Establishment Clause” in Law and Religion, ed. Leslie C. Griffin (New York: Aspen Publishers, 2010), 158.↥

- The emergence of state-sponsored humanist services might suggest that humanist pillars are actually taking shape as well. Some main components of a genuine pillar remain lacking though, e.g. a proper political party, the encompassing nature of the social services offered, etc. The notion of a pillar is quite often used in erroneous ways: equating each and every ideological division of society to pillarisation simply devoids the concept of its meaning.↥

- The most prominent example is the political constellation in Belgium between 1999 and 2007. Administrations were dominated by liberals, socialists and ecologists (in the first four-year term), as the Christian-democratic political family was exceptionally absent. This small decade is characterised by the passing of a set of important liberal ethical laws, such as the decriminalisation of euthanasia and legalisation of same-sex marriage.↥

- Franz Meffert, De sociaal-democratie tegenover godsdienst, christendom en katholieke kerk (Leiden: Futura, 1907), 33.↥

- Meine Henk Klijnsma, Om de democratie. De geschiedenis van de Vrijzinnig-Democratische Bond 1901-1946 (Amsterdam: Bert Bakker, 2008), 307.↥

- Paul Dekker and Peter Ester, “Depillarization, Deconfessionalization, and De-Ideologization: Empirical Trends in Dutch Society 1958-1992,” Review of Religious Research 37, no. 4 (June 1996): 325-326.↥

- See e.g.: Edward Royle, Radicals, Secularists, and Republicans: Popular Freethought in Britain 1866-1915 (Totowa: Rowman and Littlefield, 1980); Susan Budd, “The Loss of Faith. Reasons for Unbelief among Members of the Secular Movement in England, 1850-1950,” Past & Present 36, no. 1 (April 1967): 106-125. ↥

- Martin Pugh, Speak for Britain! A New History of the Labour Party (London: The Bodley Head, 2010), 20-21.↥

- Today, the “nones” – i.e. the large group of religiously unaffiliated, including those who identify specifically as humanists – are found throughout the entire political spectrum, similar to the British population as a whole. See: Linda Woodhead, “The rise of ‘no religion’ in Britain: The emergence of a new cultural majority,” Journal of the British Academy 4 (December 2016): 251.↥

- See: Stephen Bullivant, Religion and the New Atheism (s.l.: Brill, 2010); Samuel Bagg and David Voas, “The Triumph of Indifference: Irreligion in British Society,” 94.↥

- A major 2018 development was the introduction of training for all British asylum assessors on claims related to atheism and humanism made by asylum seekers. This training was developed and supported by Humanists UK and the All Party Parliamentary Group. See: Presentation by Richie Thompson (Director of Public Affairs and Policy at Humanists UK) at the European Parliament session “Are you a true Humanist? Free-thinkers seeking asylum in Europe,” 20-06-2019.↥

- These statuses have differed somewhat since the 1940s. The AHA for instance was a secular nonprofit after its conception in 1941 but changed into a religious “501(c)3” tax status in 1968. In the early 2000s, AHA leadership established that only 2-3 % of its members still identified as religious humanists. Subsequently, in 2007, the organisation changed back into a secular nonprofit. See: Joseph Blankholm, “Secularism and Secular People,” Public Culture 30, no. 2 (2018): 249- 263; Paul Kurtz, “Secular Humanism and Politics: When Should We Speak out?” Free Inquiry 23, no. 3 (2003): s.p.; Paul Kurtz, Ruth Mitchell, Toni Van Pelt and Tom Flynn, “It is Time for Secular Humanists to Run for Public Office,” Free Inquiry 29, no. 2 (2009): 7-8.↥

- James A. Haught, “Prodding Nones To Vote,” Free Inquiry 39, no. 4 (June/July 2019): s.p.↥

- For a brief history of the organisation see: Joseph Blankholm, “The Political Advantages of a Polysemous Secular,” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 53, no. 4 (December 2014): 778-779; R. Laurence Moore and Isaac Kramnick, Godless Citizens in a Godly Republic: Atheists in American Public Life (New York/London: W.W. Norton & Co., 2018), 154-190. Recently, political scientist Richard J. Meagher concluded that it comes as no surprise for atheist lobbying groups to have been a product of the Internet age. See: Richard J. Meagher, Atheists in American Politics: Social Movement Organizing from the Nineteenth to the Twenty-First Centuries (Lanham (MA): Lexington Books, 2018), 122. ↥

- Some isolated attempts of comparable services can be identified even before 1914, but they were not systematic at all and failed without exception. See: Jeffrey Tyssens, “Funerary Culture, Secularity and Symbolised Violence in Nineteenth-Century Belgium,” Pakistan Journal of Historical Studies 2, no. 2 (Winter 2017): 70; for the Netherlands, see: Michael Kerkhof, “Humanitas: geschiedenis en toekomst,” in Georganiseerd humanisme in Nederland: geschiedenis, visies en praktijken, ed. Bert Gasenbeek and Peter Derkx (Utrecht/Amsterdam: Humanistisch Archief/Uitgeverij SWP, 2006), 25.↥

- Callum G. Brown, “The Twentieth Century,” in The Oxford Handbook of Atheism, ed. Stephen Bullivant and Michael Ruse (Oxford: University Press, 2013), 243. ↥

- Apart from short activity statements in the annual reports of the Unie Vrijzinnige Verenigingen (Union of Secular Associations), the impact of this organisation is unclear to us. See: BE CAVA Unie Vrijzinnige Verenigingen, Moreel verslag 2002-2008, UVV22-28.↥

- Christopher Swift, Mark Cobb and Andrew Todd, ed., A Handbook of Chaplaincy Studies: Understanding Spiritual Care in Public Places (London: Routledge, 2015), 16; John Grace, “Humanist chaplains head to the UK,” The Guardian, 26-01-2010, s.p.↥

- See Niels De Nutte’s contribution to this volume.↥

- At the start of the 21st century, no humanist chaplaincy existed in Britain. This is notwithstanding a volunteer counselling program which originated in the BHA in 1965. See: Hanne Stinson, “Discrimination against non-believers in law and practice in the UK,” in Humanism & democracy in Central Europe: Coexistence of different life stances, ed. Georges Liénard et al. (Warsaw: Polish Humanist Federation, 2002), 15; BE CAVA, Archive Luc Devuyst, IHEU Congress Report 1970 ‘To Seek a Humane World’: Report of Working Party on Humanist Counselling, 42.↥

- Richard Hurley, “Chaplaincy for the 21st century, for people of all religions and none,” British Medical Journal, no. 363 (December 2018): 1. ↥

- Idem.↥

- George H. Williams and Rodney L. Petersen, ed., Divinings: Religion at Harvard; from Its Origins in New England Ecclesiastical History to the 175th Anniversary of the Harvard Divinity School, 1636-1992 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co, 2014), 124.↥

- Their first push in 2011 was supported by a resolution accepted at the IHEU World Humanist Congress in Oslo on the right to pastoral support for non-religious military personnel. In 2014, the AHA lobbied to have an amendment added to the ‘National Defense Autorization Act’. See: Anthony Barone Kolenc, “Not ‘For God and Country’: Atheist Military Chaplains and the Free Exercise Clause,” University of San Francisco Law Review 48, no. 3 (Winter 2014): 395-396. ↥

- For Belgian and Dutch jargon, see: Ine Spitters, “De morele consulent in Vlaanderen. Bericht uit België – inhoudelijke en organisatorische positie,” Praktische Humanistiek 9, no. 2 (1999): 116-123.↥

- In Belgium the State finances 334 paid humanist staff in contrast to 2801 for the Catholic church. In the Netherlands, 120 paid ‘humanistische raadlieden’ are active in care institutions, on a total of 1.000 paid staff. See: Caroline Sägesser, Jean-Philippe Schreiber and Cécile Vanderpelen-Diagré, Les religions et la laïcité en Belgique, rapport 2017 (Brussels, Université Libre de Bruxelles, 2017), 30; Steve van Velzen, “Een van de eerste humanistische geestelijke verzorgers van Engeland is een Nederlandse,” Trouw, January 9, 2019. ↥

- Luc Devuyst, “Steps towards the recognition of the non-confessional community in Belgium,” in Humanism & democracy in Central Europe: Coexistence of different life stances, ed. Georges Lienard et al. (Warsaw: Polish Humanist Federation, 2002), 36.↥

- Gillian Doyle, “Private Television in the United Kingdom: A Story of Ownership and Integration,” Private Television in Western Europe (London: Palgrave McMillan, 2013), 74-77.↥

- Lee Banville, Covering American Politics in the 21sth Century. An Encyclopedia of News Media Titans, Trends, and Controversies (Santa Barbara (CA): ABD-Clio, 2017), 266-267. ↥

- However problematic, these programmes can be considered as the first de facto recognition of seculars as a comparable agent as the religious denominations. See: Tyssens and Witte, De vrijzinnige traditie in België, 100; Pol Defosse, ed., Dictionnaire historique de la laïcité en Belgique (Brussels: Luc Pire, 2005), 233.↥

- Idem, 233; 290.↥

- DeMens.nu, Eis voor vrijzinnig humanistisch alternatief naast de erediensten: tijd voor gelijkberechtiging, accessed 31 May 2019, https://demens.nu/2017/11/30/eis-vrijzinnig-humanistisch-alternatief-naast-erediensten-tijd- gelijkberechtiging/.↥

- As of 1 January 2019 HUMAN has been granted the status of “aspirant-omroep”. If the organisation attracts 150.000 members by 31 December, it will join eight others as recognised nation-wide public broadcasters. See: Mediamonitor, NPO in 2014, accessed July 7, https://www.mediamonitor.nl/mediabedrijven/npo/npoin2014/#; A.L. den Broeder, “Mensen en media. Gedachten over humanisme en de publieke omroep,” in Humanisme. Theorie en praktijk, ed. Paul Cliteur and Douwe van Houten (Utrecht: De Tijdstroom, 1993), 340-341; Bert Gasenbeek and Piet Winkelaar, Humanisme (Kampen: Kok, 2007), 23-24. ↥

- Callum Brown, “‘The Unholy Mrs Knight’ and the BBC: Secular Humanism and the Threat to the ‘Christian Nation’, c. 1945-60,” The English Historical Review 127, no. 525 (2012): 345-376.↥

- The Guardian, 12 November 2018. ↥

- Humanists UK, Broadcasting, accessed 31 May 2019, https://humanism.org.uk/campaigns/human-rights-and-equality/ broadcasting/. ↥

- See David Nash’ contribution in this volume. ↥

- Freedom From Religion Foundation, Freethought Radio & Podcast, accessed 31 May 2019, https://ffrf.org/news/radio.↥

- Neil Genzlinger, “Believe It or Not, Atheists, TV for You,” The New York Times, August 2, 2014, C1. ↥

- Peter Derkx, “The Future of Humanism,” in The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Humanism, ed. Andrew Copson and A.C. Grayling (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015), 427.↥

- The US constitutes a marked exception to the rule, see: Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart, Sacred and Secular. Religion and Politics Worldwide (Cambridge: University Press, 2013).↥

- The support of humanists of a broader advocacy of large ethical cases (e.g. depenalization of abortion, euthanasia and the like) will surely have helped in this process. ↥

- Callum Brown, Becoming atheist (London: Bloomsbury, 2017), 162.↥

- In these divergences we do not make any value judgement whatsoever. Each position is treated as no more than an ideal-type concept championed by this or that tendency.↥

- We have placed American humanism leaning towards a pure church-state separation as they see the “Wall of Separation” as protecting the rights of unbelievers. This rings true over the past seven decades, although the AHA and Center for Inquiry (CFI) (not the Freedom from Religion Foundation, which still aims for a completely secular society) have taken some pragmatic turns. To gain the ability for their wedding officiants (for CFI these are called “secular celebrants”) to legally solemnise weddings, the AHA has used its religious tax status, and CFI proved its celebrants had special rights like existing religions. Legally, this means the AHA aims at being a hybrid to religion, while CFI aims at being analogous. See: Joseph Blankholm, “Secularism and Secular People,” 254-261; 263; Stephen Weldon’s contribution to this volume.↥

- This concept was coined by Johannes Quack, inspired by Pierre Bourdieu’s field metaphor. This relatedness can be observed as an unsuccessful disentanglement, as well as the self-identification of groups that largely busy themselves with religion. It is also used by Schröder in his research on the German case. See: Johannes Quack, “Outline of a Relational Approach to ‘Nonreligion’”, Method and Theory in the Study of Religion 26 (2014): 439-469; Johannes Quack, Cora Schuh and Susanne Kind, ed., The Diversity of Nonreligion. Normativities and Contested Relations (London: Routledge, 2019). ↥

- Cimino and Smith, “Secular Humanism and Atheism beyond Progressive Secularism,” Sociology of Religion 68, no. 4 (2007): 407-424. ↥

- Castells defines identity as “cultural attributes that are given priority over other sources of meaning” See: Castells, The Power of Identity (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), 6.↥

- Castells, The Power of Identity, 8. ↥

- Ibidem. ↥

- Cimino and Smith, “Secular Humanism and Atheism beyond Progressive Secularism,” 421. ↥

- Castells, The Power of Identity, 6.↥

- Ibidem. ↥

- With this notion, Castells refers explicitly to the work of French sociologist Alain Touraine, who sees these “subjects” as a “collective social actor through which individuals reach holistic meaning in their experience” and aim at a transformation of the collective way of life. See: Castells, , 10.↥

- Jacqueline Lalouette, La séparation des Eglises et de l’Etat. Genèse et développement d’une idée (1789-1905) (Paris: Seuil, 2005). ↥

Bibliography

- Bagg, Samuel, and David Voas. “The Triumph of Indifference: Irreligion in British Society” in Atheism and Secularity – Volume 2: Global Expressions, edited by Phil Zuckerman (New York: Preager Press, 2009).

- Banville, Lee. Covering American Politics in the 21st Century. An Encyclopedia of News Media Titans, Trends, and Controversies (Santa Barbara (CA): ABD-Clio, 2017).

- Berg, Thomas. “Lemon vs. Kurtzman. The Parochial School Crisis and the Establishment Clause” in Law and Religion, edited by Leslie C. Griffin (New York: Aspen Publishers, 2010).

- Blankholm, Joseph. “Secularism and Secular People,” Public Culture 30, no. 2 (2018).

- Blankholm, Joseph. “The Political Advantages of a Polysemous Secular,” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 53, no. 4 (2014).

- Brown, Callum G. Becoming Atheist (London: Bloomsbury, 2017).

- Brown, Callum G. “The Twentieth Century” in The Oxford Handbook of Atheism, edited by Stephen Bullivant and Michael Ruse (Oxford: University Press, 2013).

- Brown, Callum G. “‘The Unholy Mrs Knight’ and the BBC: Secular Humanism and the Threat to the ‘Christian Nation’, c. 1945-60,” The English Historical Review 127, no. 525 (2012).

- Budd, Susan. “The Loss of Faith. Reasons for Unbelief among Members of the Secular Movement in England, 1850-1950,” Past & Present 36, no. 1 (1967).

- Bullivant, Stephen. Religion and the New Atheism (s.l.: Brill, 2010).

- Castells, Manuel. The Power of Identity (Chichester: Wily-Blackwell, 2010).

- Cimino, Richard, and Christopher Smith. “Secular Humanism and Atheism beyond Progressive Secularism,” Sociology of Religion 68, no. 4 (2007).

- Conze, Werner. “Säkularisation, Säkularisierung” In Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe. Historisches Lexikon zur politisch-sozialen Sprache in Deutschland V, edited by Brunner O., Conze W. and Kosseleck R. (Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, 1984).

- Copson, Andrew. Secularism: Politics, Religion, and Freedom (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017).

- den Broeder, A.L. “Mensen en media. Gedachten over humanisme en de publieke omroep” in Humanisme. Theorie en praktijk, edited by Paul Cliteur and Douwe van Houten (Utrecht: De Tijdstroom, 1993).

- Defosse, Pol, ed. Dictionnaire historique de la laïcité en Belgique (Brussels: Luc Pire, 2005).

- Dekker, Paul, and Peter Ester. “Depillarization, Deconfessionalization, and De-Ideologization: Empirical Trends in Dutch Society 1958-1992,” Review of Religious Research 37, no. 4 (1996).

- Derkx, Peter. “The Future of Humanism” in The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Humanism, ed. Andrew Copson and A.C. Grayling (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015).

- Devuyst, Luc. “Steps towards the recognition of the non-confessional community in Belgium” in Humanism & democracy in Central Europe: Coexistence of different life stances, edited by Georges Lienard e.a. (Warsaw: Polish Humanist Federation, 2002).

- Doyle, Gillian. “Private Television in the United Kingdom: A Story of Ownership and Integration” in Private Television in Western Europe, edited by Karen Donders, Caroline Pauwels and Ja Loisen (London: Palgrave McMillan, 2013).

- Edwards, Ben. “The Godless Congress of 1938: Christian Fears About Communism in Great Britain,” Journal of Religious History 37, no. 1 (2013).

- Gasenbeek, Bert, and Babu Gogineni, ed. International Humanist and Ethical Union. 1952-2002. Past, Present and Future (Utrecht: De Tijdstroom, 2002).

- Gasenbeek, Bert, and Peter Derkx, ed. Georganiseerd humanisme in Nederland: geschiedenis, visies en praktijken (Amsterdam: Het Humanistisch Archief Utrecht & Uitgeverij SWP, 2006).

- Gasenbeek, Bert, and Piet Winkelaar. Humanisme (Kampen: Kok, 2007).

- Genzlinger, Neil. “Believe It or Not, Atheists, TV for You,” The New York Times, 2 August 2014.

- Grace, John. “Humanist chaplains head to the UK,” The Guardian, 26 January, 2010.

- Hasquin, Hervé. “Is Belgium a laïque State?” in Separation of Church and State in Europe, edited by Fleur De Beaufort e.a. (The Hague: European Liberal Forum, 2008).

- Haught, James A. “Prodding Nones To Vote,” Free Inquiry 39, no. 4 (2019).

- Hooghe, Marc. “Vijftig jaar na mei ’68: ontzuiling in de Lage Landen,” Ons Erfdeel 51, no. 2 (2008).

- Hurley, Richard. “Chaplaincy for the 21st century, for people of all religions and none,” British Medical Journal, no. 363 (2018).

- Huyse, Luc. De verzuiling voorbij (Leuven: Kritak, 1987).

- Jones, Robert P., and Daniel Cox, ed. America’s Changing Religious Identity. Findings from the 2016 American Values Atlas (Washington D.C.: Public Religion Research Institute, 2017).

- Joppke, Christian. “Beyond the wall of separation: Religion and the American state in comparative perspective,” International Journal of Constitutional Law 14, no. 4 (2016).

- Joppke, Christian. The Secular State Under Siege. Religion and Politics in Europe and America (Cambridge: Polity, 2015).

- Kerkhof, Michael. “Humanitas: geschiedenis en toekomst” in Georganiseerd humanisme in Nederland: geschiedenis, visies en praktijken, edited by Bert Gasenbeek and Peter Derkx (Utrecht/Amsterdam: Humanistisch Archief/Uitgeverij SWP, 2006).

- Klijnsma, Meine Henk. Om de democratie. De geschiedenis van de Vrijzinnig-Democratische Bond 1901-1946 (Amsterdam: Bert Bakker, 2008).

- Kolenc, Anthony Barone. “Not ‘For God and Country’: Atheist Military Chaplains and the Free Exercise Clause,” University of San Francisco Law Review 48, no. 3 (2014).

- Kurtz, Paul. “Secular Humanism and Politics: When Should We Speak out?” Free Inquiry 23, no. 3 (2003).

- Kurtz, Paul, Ruth Mitchell, Toni Van Pelt and Tom Flynn. “It is Time for Secular Humanists to Run for Public Office,” Free Inquiry 29, no. 2 (2009).

- Lalouette, Jacqueline. La séparation des Eglises et de l’Etat. Genèse et développement d’une idée (1789-1905) (Paris: Seuil, 2005).

- Laqua, Daniel. The Age of Internationalism and Belgium 1880-1930. Peace, Progress and Prestige (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013).

- Meagher, Richard J. Atheists in American Politics: Social Movement Organizing from the Nineteenth to the Twenty-First Centuries (Lanham (MA): Lexington Books, 2018).

- Meffert, Franz. De sociaal-democratie tegenover godsdienst, christendom en katholieke kerk (Leiden: Futura, 1907).

- Moore, Laurence R., and Isaac Kramnick. Godless Citizens in a Godly Republic: Atheists in American Public Life (New York/London: W.W. Norton & Co., 2018).

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. Sacred and Secular. Religion and Politics Worldwide (Cambridge: University Press, 2013).

- Pew Research Center, May 12, 2015 “America’s Changing Religious Landscape.”

- Pew Research Center, May 29, 2018 “Being Christian in Western Europe.”

- Pugh, Martin, Speak for Britain! A New History of the Labour Party (London: The Bodley Head, 2010).

- Quack, Johannes. “Outline of a Relational Approach to ‘Nonreligion’,” Method and Theory in the Study of Religion 26 (2014).

- Quack, Johannes, Cora Schuh, and Susanne Kind, ed. The Diversity of Nonreligion. Normativities and Contested Relations (London: Routledge, 2019).

- Royle, Edward. Radicals, Secularists, and Republicans: Popular Freethought in Britain 1866-1915 (Totowa: Rowman and Littlefield, 1980).

- Sägesser, Caroline, Jean-Philippe Schreiber and Cécile Vanderpelen-Diagré. Les religions et la laïcité en Belgique, rapport 2017 (Brussels, Université Libre de Bruxelles, 2017).

- Schröder, Stefan. Freigeistige Organisationen in Deutschland: Weltanschauliche Entwicklungen und Strategische Spannungen nach der Humanistischen Wende (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2018).

- Spitters, Ine. “De morele consulent in Vlaanderen. Bericht uit België – inhoudelijke en organisatorische positie,” Praktische Humanistiek 9, no. 2 (1999).

- Stinson, Hanne. “Discrimination against non-believers in law and practice in the UK” in Humanism & democracy in Central Europe: Coexistence of different life stances, edited by Georges Lienard et al. (Warsaw: Polish Humanist Federation, 2002).

- Swift, Christopher, Mark Cobb and Andrew Todd, ed. A Handbook of Chaplaincy Studies: Understanding Spiritual Care in Public Places (London: Routledge, 2015).

- Tielman, Rob. Humanisme als zelfbeschikking. Levensherinneringen van een homohumanist (Breda: Papieren Tijger, 2016).

- Tyssens, Jeffrey. “Funerary Culture, Secularity and Symbolised Violence in Nineteenth-Century Belgium,” Pakistan Journal of Historical Studies 2, no. 2 (2017).

- Tyssens, Jeffrey, and Els Witte. De vrijzinnige traditie in België. Van getolereerde tegencultuur tot erkende levensbeschouwing (Brussels: VUBPRESS, 1996).

- Tyssens, Jeffrey, and Petri Mirala. “Transnational Seculars: Belgium as an International Forum for Freethinkers and Freemasons in the Belle Epoque,” Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Filologie en Geschiedenis/Revue belge de Philologie et d’Histoire 90, no. 4 (2012).

- van Velzen, Steve. “Een van de eerste humanistische geestelijke verzorgers van Engeland is een Nederlandse,” Trouw, 9 January 2019.

- Willemyns, Roland. De term vrijzinnigheid. Een eerste poging tot semantisch-vergelijkend onderzoek van het woordveld (Antwerp: Humanistisch Verbond, 1980).

- Williams, Daniel K. God’s Own Party. The Making of the Christian Right (Oxford, University Press, 2010).

- Williams, George H., and Rodney L. Petersen, ed. Divinings: Religion at Harvard; from Its Origins in New England Ecclesiastical History to the 175th Anniversary of the Harvard Divinity School, 1636-1992 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co, 2014).

- Woodhead, Linda. “The rise of ‘no religion’ in Britain: The emergence of a new cultural majority,” Journal of the British Academy 4, (2016).

All rights reserved. No parts of this article may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Tyssens, Jeffrey and De Nutte, Niels. “Comparative Humanisms: Secularity and Life Stances in the Post-War Public Sphere” In Looking Back to Look Forward, edited by Niels De Nutte and Bert Gasenbeek, 151-171. Brussels: VUBPress, 2019.

This page was last updated on 18 January 2021.